![]()

by Mary Ellen Donald, nationally acclaimed author, instructor, & performer in Middle Eastern percussion

Dancers, you are performing and playing finger cymbals to a combination of melody and drum beat. The drummer is stringing together variations of distinct identifiable rhythmical patterns. If you train your ears to distinguish one rhythm from another, detecting the unique underlying accent pattern of each one, you will hold the key to being at one with your music in your performance. Such rhythmical expertise will bring authority and excitement to your dancing and cymbal playing.

You dont have to master fifty rhythms to be prepared for a cabaret belly dance routine. You only have to become very familiar with a few major rhythms in order to do justice to the music to which you perform. Before going further, I would like to point out that a cabaret routine can take many different forms. A very common one, the one Im using as a reference point for this article, on the short side, goes as follows: entrance piece, three to five minutes complex, containing a number of rhythm changes and stops and spicy breaks to show off the dancers expertise; slow piece, three or four minutes, sensuous music to which the dancer often displays her creativity with the veil; drum solo, two to four minutes, where only percussion instruments are playing, full of spices and off-beat accents, providing an opportunity for playfulness and intense shimmies; finale piece, usually under one minute, very lively exit music. If going out for tips is appropriate and called for, then lively tip music would be inserted between the drum solo and the finale piece.

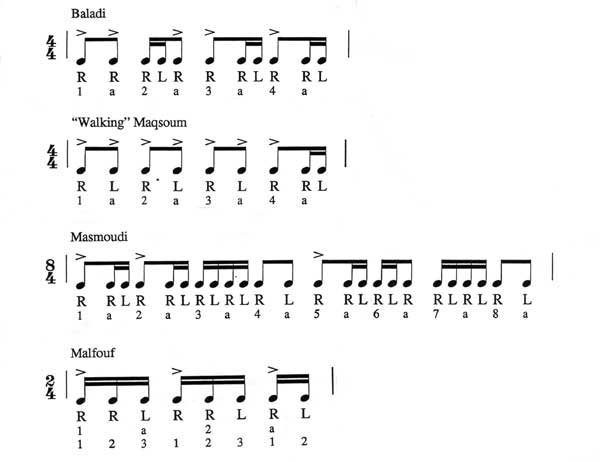

Baladi, maqsoum, masmoudi, and malfouf are rhythms often found in entrance pieces (such as Lailet Hob, Hani and Tamrihinna). Baladi and maqsoum share the same accent pattern, but maqsoum is played faster and usually begins with a doum, tek (low tone, high tone) instead of the doum, doum (two low tones) that begin baladi. In a way, it is a stretched out baladi. Masmoudi contains eight counts. Baladi has four. They both share the same doum accents on the drum; two in the beginning and one in the middle. In conservatories of music in Arab countries the rhythm we call baladi here is called masmoudi saqhire or small masmoudi. The rhythm that we call masmoudi, they call masmoudi kabir, or big masmoudi. The malfouf rhythm is not related to those mentioned above. It is a short catchy rhythm usually played rather fast.

For dancers and drummers alike the task connected with performing entrance pieces is to know the melodies contained in them inside and out, and to know which rhythms accompany each melody. Dancers who perform oblivious to the rhythm changes in their music, dancing the same steps and playing the same cymbal patterns through baladi, malfouf, and masmoudi sections, miss a great opportunity to bring variety to their performance and express the excitement within the music.

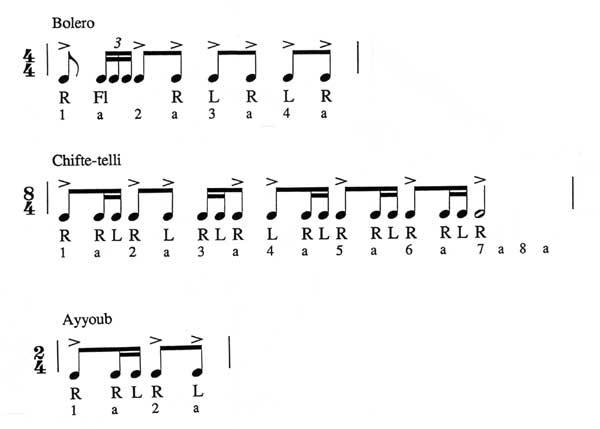

The slow section of the dance routine is usually accompanied by either the bolero or chifte-telli rhythms. The bolero usually accompanies a lyrical song (such as Erev Shel Shoshanim and Norits Karoon Yegav, the chifte-telli usually accompanies a melodic improvization (taqsim), that is, not a fixed melody. For the most part dancers are playing with veils and not playing cymbals during this section. Nevertheless, it is important for dancers to know the structure of bolero and chifte-telli so that their movements can reflect the unique flavor of each.

During the drum solo, a tambourinist or a drummer with a deep toned drum is providing a rhythmical back-up, often the maqsoum rhythm, while the lead drummer links a series of spices, not specific Middle Eastern rhythms, often improvised, sometimes memorized. Usually these pieces are played two or four times in a row to help dancers have a better chance of catching the accents in their hips. A good way for dancers to prepare for performing to improvised drum solos would be to listen to many drum solos over and over so that typical patterns can be recognized.

Finale sections (such as Toutah,Tafta Hindi or Hijaz Finale) are usually short and sweet, often beginning at a moderate tempo, and ending up very fast. Ayyoub and malfouf are the main rhythms accompanying this section. If dancers are going out for tips before the finale, then moderate tempo music accompanied by the maqsoum rhythm is a popular choice.

Knowing the rhythms that you are dancing to is an integral part of becoming a first rate dancer. Of course, you can know the rhythms without knowing their names, but if you know their names, you can communicate more clearly with your accompanying musicians. In closing, Id like to share a bit of inside information, which is probably not much of a secret. If musicians see that dancers know their music very well, changing dance steps and cymbal patterns according to changes in rhythm, they respect the dancers much more and are more likely to play better music.

Below you will find just one example for each of the rhythms mentioned in this article. There are many more variations for these rhythms. I would like to point out that sometimes it is very effective to not play on your cymbals the exact rhythm that the drummer is playing, but rather play across the rhythm; that is, some pleasing combination of alternating strokes, right, left, right, left and the belly dance gallop right left right, right left right.

Played same as baladi but faster.

Copyright 2009 Mary Ellen Donald - All

Rights Reserved

Page Design & Web Goddess

Yolanda

- Last Revised:

12/09/08